From The Chronicle Review, January 20, 2012

By Christopher Jon Sprigman

On Wednesday thousands of scholars joined millions of people around the world in online protest of two proposed laws, the

Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the

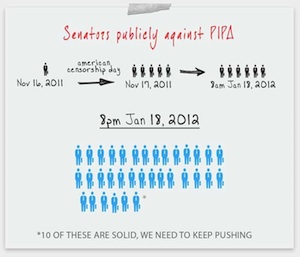

Protect IP Act (PIPA). SOPA and PIPA would, in the view of many observers, authorize wide-ranging online censorship in the guise of stopping copyright infringement. So far, the protest appears to have been a success: Congressional support for the proposed laws is crumbling.

On that same day, the U.S. Supreme Court issued an opinion in a copyright case that may be just as important as SOPA and PIPA—and potentially just as harmful to the interests of scholars, librarians, and archivists. In

Golan v. Holder, a group of conductors, educators, film distributors, and others challenged the constitutionality of Congress's decision in 1994 to remove millions of books, films, songs, and other creative works, mostly foreign, from the public domain and "restore" their copyrights. It did so to conform to an international agreement, although it is far from clear that the move was required to put the United States in conformity. Some of the works taken from the public domain and put back under copyright are very famous; they include Prokofiev's "Peter and the Wolf," the symphonies of Shostakovich, Picasso's "Guernica," and the English films of Alfred Hitchcock.

The Golan plaintiffs argued that Congress lacked the power under the Constitution's Copyright and Patent Clause to re-copyright those works, and also that the move violated the First Amendment. How? By imposing copyright burdens on free speech where none had existed before.

In a 6-2 opinion written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (with Justices Stephen G. Breyer and Samuel A. Alito Jr. dissenting), the court found that "[n]either the Copyright and Patent Clause nor the First Amendment ... makes the public domain, in any and all cases, a territory that works may never exit."

I should make clear that I have no claim to objectivity in this case. I was one of the lawyers who represented the plaintiffs in Golan, and, more to the point, I have long believed that copyright restoration is both unlawful and bad policy. The court's opinion in Golan hasn't convinced me otherwise.

Let's take the Copyright and Patent Clause argument first. That part of the Constitution authorizes Congress to make patent and copyright laws, but requires that if Congress does so, it must restrict authors' and inventors' ownership of ideas and creative expression to "limited Times." That is, there can be no copyright or patent that lasts forever. And that makes good sense—copyright's purpose is to encourage the creation of new artistic and literary works by offering creators ownership of those works. But encouraging new works does not require perpetual ownership. And there are, moreover, important public interests in the widest possible access to creative works: to help spread learning, and to encourage new creators to build on what's been produced before. The Constitution sensibly balances those goals by providing for private rights, but limiting them, and thereby creating a constitutionally mandated public domain.

The Golan plaintiffs argued that pulling works like "Peter and the Wolf " out of the public domain and putting them back under private ownership violated the "limited Times" restriction. And that argument is not abstract, but very practical. A copyright term that can expire but then can be reactivated at any time isn't "limited." If Congress can restore expired copyrights, then no one can rely on the public-domain status of any particular work. Indeed, Congress could auction off the public domain to the highest bidder. And that destroys much of the public domain's value, because now any use of a public-domain work—either as part of a new work (say, another modern retelling of a Jane Austen novel) or as part of an archived collection in a library—can later be subject to revived copyright claims and demands for licensing payments. That loss of certainty will chill use of the public domain, and therefore is inconsistent with the purposes of the "limited Times" requirement.

The court rejected that argument, holding instead that "limited Times" simply means "not forever." The term of restored copyright, the court noted, is not perpetual, and therefore Congress acted within its power. And as for the possibility that Congress would enact more restorations to achieve perpetual copyright on the installment plan, the court held that the possibility of this "hypothetical legislative misbehavior" was not worth considering.

The Golan plaintiffs' First Amendment claim fared even worse. It was built on something the Supreme Court said almost a decade ago in Eldred v. Ashcroft. Eldred was the case in which the Supreme Court affirmed Congress's 20-year extension of already-existing copyrights. The court rejected a First Amendment challenge to that change, holding that a long history of prior copyright extensions meant that the latest was constitutional. But the court issued an important caveat. Where Congress does not act in accordance with history, but instead alters copyright's "traditional contours," courts must conduct a more searching First Amendment review to ensure that whatever Congress has done does not burden speech in ways that cannot be justified.

Until today, we haven't known much about what the "traditional contours" test meant. AfterGolan we know that it means almost nothing.

There's no question that copyright restoration burdens speech; before Congress acted, we were all free to copy "Peter and the Wolf," to perform it, or to use its melodies in our own compositions. After restoration we can't do any of that without permission—which costs money. And there is no history of copyright restoration comparable to the history of copyright term extensions in Eldred.That doesn't matter, the court said in Golan, because Congress is free to restore copyrights without First Amendment review so long as doing so doesn't erase copyright's fair-use doctrine (a limited exception to copyright for teaching, criticism, and some other purposes) or its distinction between expression (copyrightable) and pure ideas (not copyrightable). The fair-use doctrine and the idea-expression distinction are the only "traditional contours" of copyright that Congress cannot disturb.

That's cold comfort to the artist who wishes to use a re-copyrighted work, or the archivist who wishes to digitize it and is now restricted to using whatever little snippet might qualify as "fair." As for the idea-expression distinction, in many cases that's no use at all. Major metropolitan orchestras will be able to afford to license the Shostakovich's symphonies that were once in the public domain. But less well-heeled regional orchestras or high schools won't. And it matters little that those orchestras remain free to communicate the "ideas" behind Shostakovich's work. What matters is the music, and that's back under copyright.

So, what's next? For teachers, scholars, artists, librarians, and others concerned with Congress's incessant expansion of the scope and duration of copyright, Golan makes clear that we can expect no help from the Supreme Court. Which brings me back to where I started—Wednesday's huge, and thus far effective, protests against SOPA and PIPA. Those protests demonstrated that the tech industry, allied with the online grass roots, could overcome Hollywood's pro-copyright lobbying muscle. It's too early to say for sure, but it's possible that those protests marked the end of Hollywood's and the publishing and music industries' lock on copyright policy. Someone might test that by proposing that legislation be offered to return to the public domain all the works that the Supreme Court says Congress had the right to take out in 1994. Those works belong to all of us. And I, for one, want them back.

Christopher Jon Sprigman is a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

A message from CREDO Action:

A message from CREDO Action: